"Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning."

Winston Churchill

I debate a bit, gets me into trouble sometimes, but it seems to be something that I'm wired to do, to think about things, to discuss things. I try to keep things above the belt, I really do. I'm human, my buttons get pushed sometimes and I've probably been known to react a time or two, but I really do try to keep an even keel and not attack people personally, even when I feel like I'm being personally attacked myself.

And it's funny, I remember years ago, struggling as I often do living as a typically polite Canadian in a politically correct climate, oh so afraid of offending someone. That's how we are, right? We Canadians are so deathly afraid of offending someone, and yet I found myself in an awkward position as a Christian, seeing my deeply held convictions chewed up and spit in my face repeatedly, and yet constantly being told by the culture that surrounded me, you do not question other people's beliefs, you dare not! All religions are the same doncha' know, it's cultural, so don't ye then therefore judge (sigh).

I'm looking out the window here as I pause for a moment. It was probably around that same time, while struggling to understand how my faith fit into things, while realizing my guilt by association, that I was listening to a local talk show host who I still miss. He's not on the air anymore. His name is Michael Harris. But I remember Harris saying, and I'm paraphrasing, that the next time someone attacks you personally, be sure to tell them to address your point first, something to that effect. And I remembered that, and I have found that to be often the case, that when people resort to ad hominem attacks it's because they are out of arguments and are grasping at straws. They don't know what to say next, and so they resort to attacking the person.

Well, recently I was having a discussion with someone and I had no idea why the person seemed to be doing this constantly over a period of days if not weeks. We would begin a discussion, which would soon dissolve into some problem or another with me personally. I think now that the anger that I was picking up on was really being directed at the far right, which I do not associate myself with politically. I'm a social conservative at heart, and probably conservative leaning, but not to the point of thinking that other people with different views or perspectives could not possibly have a point. I'm not a partisan, in short, or try not to be, and am more interested in understanding issues and discussing issues than I am in clinging to a rigid partisan position. I've also come to a place over the years more and more where I don't see the current culture wars working and am more interested in dialogue and supporting individual rights as a way to build bridges and work constructively with people whom I may not agree with (their emphasis), but I think there is commonality to be found. Unfortunately, because we are so often focused on the things we disagree on, we never get around to finding our points of commonality, or the areas where I think we could learn to work together.

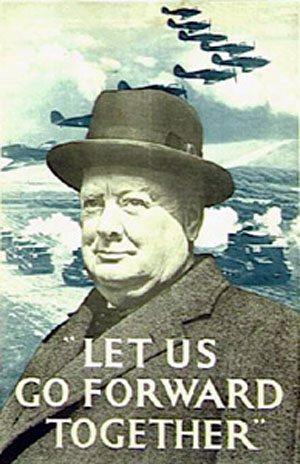

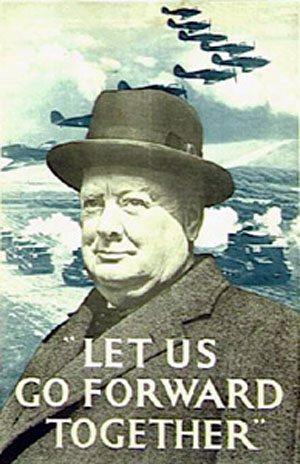

But it was after one of these conversations with this individual, while in the bewilderment that followed yet another bitter personal attack and I could not seem to reason with the person for love or money (lol), while dealing with a faltering appliance and walking upstairs from the basement in attempting to do laundry in spite of the same faltering appliance, a variation on Churchill's words came to my mind with ensuing existential dread, "the beginning of the end," and it pretty much summed up how I felt in that moment. I'd always been intrigued by Churchill's famous quotation and wondered what he meant when he said those words. I paused for a moment and then continued up the stairs after deciding to look it up. The phrase was spoken by Churchill in 1942, in the middle of a world war that had followed the bloodbath of the first world war that was supposed to end wars. The Allies had just scored their first major victory under the leadership of a man who if he had not stood up to Nazi aggression, the world today might look very different. If I'm interpreting Churchill's words correctly, he seems to be saying, it's not over yet folks, but we are further than we were before. It was "the end of the beginning."

Though not entirely related, there's something about being dragged through the mud that makes one look inward. In recalling Churchill's words, I was reminded of my own beginnings, who I really am at the end of the day. The kid who always felt like I never fit in anywhere, not in school, not at home, not at work, not in church, and how it wasn't until I began working with the mentally disabled and found in a community of people what seemed to me to be a glimpse of heaven, where the last will be first and the first will be last. It reminded me that no matter what people say, or what people think, at the end of the day I am someone who found a home in the kingdom of heaven, long before I found a home anywhere else.

And that's who I remain, someone who found a home in the values of Christ, but who developed an interest in apologetics because I also found that as much as I desired to communicate something of that message, everywhere I turned I found people who couldn't hear that message because of all the baggage that Christianity has acquired in the last 2000 years. It wasn't about the sermon on the mount anymore, or love your neighbour or do unto others, as much as it had become about Crusades and Inquisitions and sexual abuse and cultural clashes and witch burnings and genocide. So whaddaya do?

You begin to dialogue with people where they are at. You begin to address their concerns, their anger, their fear, their questions. But you know what pains me? It pains me that I don't think it is all negative, Christian history that is. And I don't think it's a coincidence that the places that are considered by many to be the best places to live in the world today are historically Judeo-Christian. Why is that? I also don't think it's a coincidence, the values of altruism and service to the poor, the egalitarianism and human rights concerns of the western world. Not that we're necessarily consistent or have a perfect track record of human rights ourselves, but I do think that the secularist or skeptic must begin to address the source of those values on a purely materialistic worldview. As an article that was recently sent my way seems to highlight, in which visiting philanthropists from the west to China, found that they could not just expect wealthy Chinese individuals to care for people outside their family. That's pretty much what we should expect on a naturalistic worldview is it not?

http://www.forbes.com/sites/china/2010/10/04/turning-down-gates-buffett-philanthropy-in-china-requires-for-profit-social-enterprise

Personally, I think it's the remnant of the influence of the Bible on our culture. In quoting Christian academic Nicholas Wolterstorf, who I have heard say that when you read other ancient literature you do not see the same concern expressed for the orphan, the widow and the immigrant, as you see in the pages of the Old and New Testaments. A continual call to justice for all people, rich and poor, male and female, slave and free, the height of altruism being modeled in God himself, who offers his own life for the salvation of all of humanity.

http://www.openbible.info/topics/serving_the_poor

But here's the question I come to, why is it that in a culture that claims to be all about western rationalism and the values of the enlightenment, the height of reason in world history, where people are more educated than ever before, that well-read westerners seem to have such a hard time defending their positions rationally, without resorting to ad hominem attacks that seem to have become so prevalent in the discourse of our day? Could it be that it is not so easy to argue for egalitarian principles on a naturalistic worldview? Could it be also, that while something has been lost of our spiritual heritage, something yet remains? The average person has a sense that we should care about those who are less fortunate; we should defend the rights of others, but because they don't know the foundation of those values (it's not like they are being taught to read the Bible of all things), they remain at a loss in expressing or defending the values that our human experience knows to be true, when push comes to talking louder.

And so the question remains, how really do you begin to defend altruism if everything that surrounds us is purely material, a mere competition for resources to no ultimate end? How do you begin to defend human rights or human dignity or the intrinsic worth of all human beings on a purely mechanistic worldview that continues to run down with no objective meaning? Whatever leads to human flourishing, say some. But what is human anyway, if human is a theological concept? And what are values, if values are subjective to begin with? Who decides? It's all culture, remember? Who are we to judge, one set of values over another?

May I suggest, I think it is the ultimate lack of depth of secularism as a worldview, as more and more the Judeo-Christian cultural backdrop can no longer be assumed or referenced, that results in so much of the frustration that we see in public discourse. We've cut ourselves off from any spiritual frame of reference, any kind of objective or shared meaning. So what do we do, we assume from what remains of a Judeo-Christian spiritual tradition a common value or shared ethical foundation. But how much longer can we assume in a multicultural milieu, where some people are appalled by polygamy and female circumcision or gender selective abortion and some people think it's the norm? And on what basis do we continue to assume, if every value or lack thereof is assumed to be as good as the next one? That is what I see in so much public discourse, an assumption that the other side of an issue ought to see the point in question, but what if they don't? How is one to argue otherwise without a common point of reference? And so when one side of an issue doesn't come at it from the same angle or core value the frustration becomes personal, for lack of a shared point of reference to appeal to or to motivate the listener.

I have noticed in my discussions with Muslims, more specifically, and I say that simply because I find myself in what you might call inter-religious dialogue with Muslims quite a bit these days. They seem to have different points of reference and a different scriptural authority which has come to form the cultural backdrop of the Muslim world. The thing that puzzles me so much in these discussions, generally speaking of course, is what appears to be an inability or unwillingness to question much of Islamic history and practice. I don't understand this as a westerner, but I have a running theory which can best be described in asking, how far can you go in critiquing a worldview that is totalitarian in nature? If everything relates to the whole of an ideology in some way because it can't be separated and demands submission to it's higher authority in all matters of personal life and politics, where is the room for criticism?

I think there is something about the way in which Jesus said that his kingdom is not of this world, that has allowed Christians to begin to see the complexity of questions regarding minorities or separation of church and state or other issues for what they are, complex. We can look back and say yeah, maybe that wasn't such a good idea or maybe we need to do some things differently. But how do you begin to do that if many of those actions or cultural practices are rooted in the example or teaching of your founder, who is seen as the ideal person and role model as in the case of Muhammad to Islam? Also, how do you begin to recognize the rights of the individual as separate from the state if the place of the individual is in submitting to the governing totalitarian ideology, as in Islam, whether the person then submitting to the Islamic state is Muslim or not?

In nearing close here, maybe I've asked more questions than I've offered answers or solutions, but I do think these are relevant questions as more and more we have competing worldviews in the western world. Surely there are challenges that accompany a growing diversity of worldviews, but just as surely there is a growing opportunity for dialogue and an exchange of ideas as never before. And that is my hope in a changing world, that regardless of our differences we still have the freedom to communicate in the western world, thankfully. And that remains the nature of a free society, as I occasionally remind myself, where we are free to agree or disagree, free to offend each other and free to change our mind or apologize when appropriate.

In acknowledging this growing diversity, I accept that I should not expect a sort of homogeneous recognition of our western spiritual heritage in a formal or political sense. I'm not asking for that on an institutional level to be very clear. I say this because where I see people asking or demanding an institutional Christianity I see political polarization which is what I'm trying to get beyond here. Yet having said that I wonder if there is a way in which there can be a sort of informal understanding of that which our Judeo-Christian spiritual heritage has given us, as a way of maintaining core values in our culture. It does seem fair to ask, why does it seem to be considered an affront to make mention of the Bible or to quote the Bible, where I doubt it would be deemed offensive to quote other sacred literature in a related discussion of ethics or tradition. Is quoting the Bible that different from quoting Shakespeare or Aristotle in public discourse, for surely the Bible has had as much if not more influence on western culture as have the Greeks or Shakespeare in that sense. I do find myself wondering, if we are not free to make reference to our western spiritual traditions, even on a cultural level, where do we go from here?

I'm sure there are lots of people who think that we do have common values in the west, and I agree that I see this in my daily life as well. There's still some assumptions about the way things ought to be hovering in the air. But I also wonder if this sense of shared values is eroding, when I think about the culture I remember growing up in, where I can't imagine anyone objecting to the singing of O Canada for example, or when I listen to a speech of Winston Churchill vs. the animosity and polarization that I see today which seems to be increasing rather than lessening. Nothing is simple, but if I am right in thinking that our historical Biblical values of concern for the poor and a sense of personal responsibility to a holy God are not just the way of the world, what will happen when those values are erased for good, or any memory of those once largely shared values? I suppose human history will returns to it's roots, conquest and defeat. Privilege and oppression. Hierarchy. The natural order of things.

Maybe that sounds a bit alarmist, all things considered, but in concluding, as much as I know it's not the end, because I believe in the presence of something bigger in all this, nor is it so much the end of the beginning as in the way that Churchill was expressing in his time... I do find myself wondering sometimes if our present culture's insistence on destroying every last recognizable trace of our spiritual heritage is the beginning of an end, or the end of a beginning. A beginning that started so long ago, in a people who understood that it wasn't so much about reason, that was Athens, or glory, that was Rome. It was about the relationship of a people to a Holy God, who insisted on a higher standard. As much as I know we haven't always lived up to that standard, I believe that spiritual history has given us a foundation for our culture, for ethics, for service, for the value of the individual person, created in God's image. Reason, in contrast, doesn't necessarily lead you to morality, a consistent standard or expectation of behavior. That would require a fixed point of reference, an end for the beginning.

Thanks for listening,

M.A. Harvey

Links:

transcript: "The end of the beginning" speech:

http://www.winstonchurchill.org/learn/speeches/speeches-of-winston-churchill/1941-1945-war-leader/987-the-end-of-the-beginning

audio: "The end of the beginning" speech: Winston Churchill

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aPMw6vuhV-4

Image: Winston Churchill